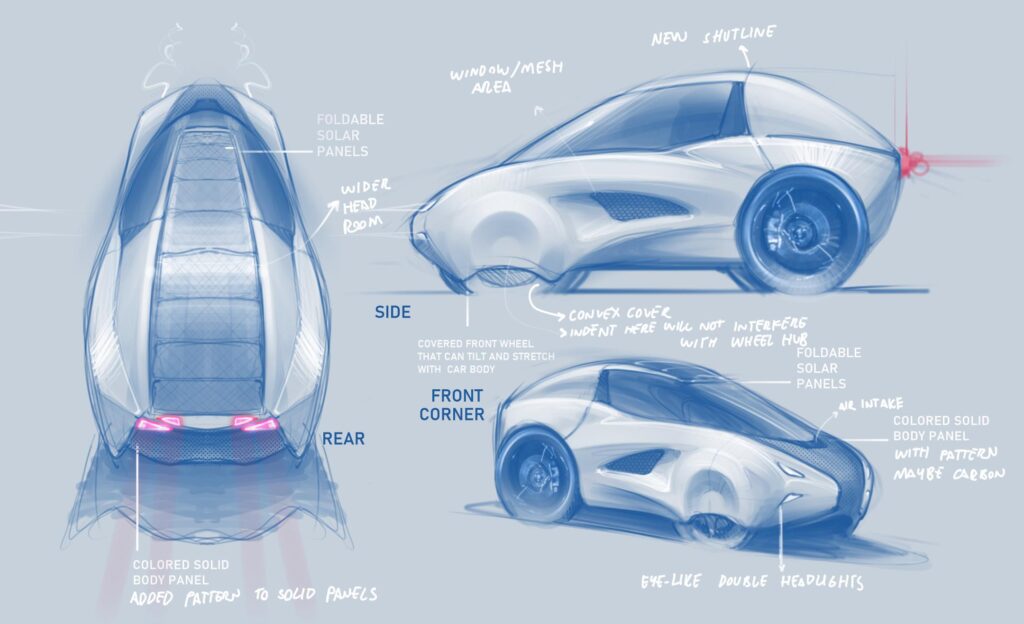

Why does the Turanga Velo look the way it does? Designing a product that is the platypus of the mobility world doesn’t have much precedent to draw upon. The Consumer Reports issue comparing all the tilting, four-wheeled, 1+1 seater micromobility vehicles has yet to hit newsstands. Just cycling through the permutations of theme, form, proportion, details, materials, and finishes would result in millions of ways a product can present itself to the world. How to pick just one?

The art of product development is as much about what to build as how to make it work. While engineers are concerned with the nuts and bolts of execution, designers articulate the vision and define the problems that must be overcome to achieve it.. While difficult enough a task when refining an existing product, starting from a clean sheet requires extra negotiation. Not enough ambiguity? Then add designing for the fickle tastes of the consumer market and watch the product vision blur into a miasma of ambiguity. How do you even start?

Guiding philosophies are helpful to narrow down the infinite solutions. At the dawn of the modern age of industrial design almost a century ago, MAYA was seen as the way forward. Coined by Raymond Loewy in the mid-20th century, MAYA declares that products designed to shape the future take steps forward, but not so many as to alienate the prospective buyer. The rationale certainly makes sense, but who’s to say how much advancement is too much? During Loewy’s time, the consumer market was considered a monoculture, which it is most certainly not today, so assessing the opinion of the archetypal consumer isn’t possible. Also, implicit in the phrasing is a dialing back of the original vision, a blunting of the point of the design to avoid offending a public considered too provincial to appreciate the real thing.

Leaving these judgments solely in the designer’s hands became too heavy a burden. So while MAYA was useful for its time, a new framework was needed. In time, the designer’s singular approval was gradually displaced by consumer clinics. Believing that massive sales are unlocked by eliminating provocative elements that could raise the collective eyebrow of a wider audience, the results were only low-energy, forgettable designs that sold reasonably well but lacked enough character to be memorable, only diluting the brand’s value.

Where to go from here? During a seemingly unrelated search for resources to turn around another winless season for the kids soccer team I coach, I was surprised to come across a chapter in Adam Grant’s book “Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things,” that spoke to the struggle of distilling an idea from a million possibilities. Struggling to make his writing achieve his self-imposed standard of perfection, Grant reframes his goal as striving towards towards excellence and to have his drafts receive enthusiastic “I love it!” endorsements from his trusted circle of reviewers who are familiar with his mission. A critical mass of “I love it!’ from his reviewers, who understand what he’s trying to achieve, is a strong indicator that the draft is excellent and has enough punch to move forward with an MLP (Minimum Lovable Product).

Grant’s definition of the term comes from a different angle, but using lovable as a metric lights the way past MAYA’s limitations and fulfills a purpose with enthusiasm instead of sandbagging an imagined optimum. So just capture the essence of love in your product design and you’ve got it made! Easy-peasy right?

I will go out on a limb here and claim that love for non-human entities is a lot easier to fulfill, though it produces much worse art

People fall in love with a product because it meets you where you are at that moment and fulfills the aspiration of what you wish to become. Its compelling features provide at least a respectable level of utility but the real hook is the emotional resonance it triggers.

…to be continued