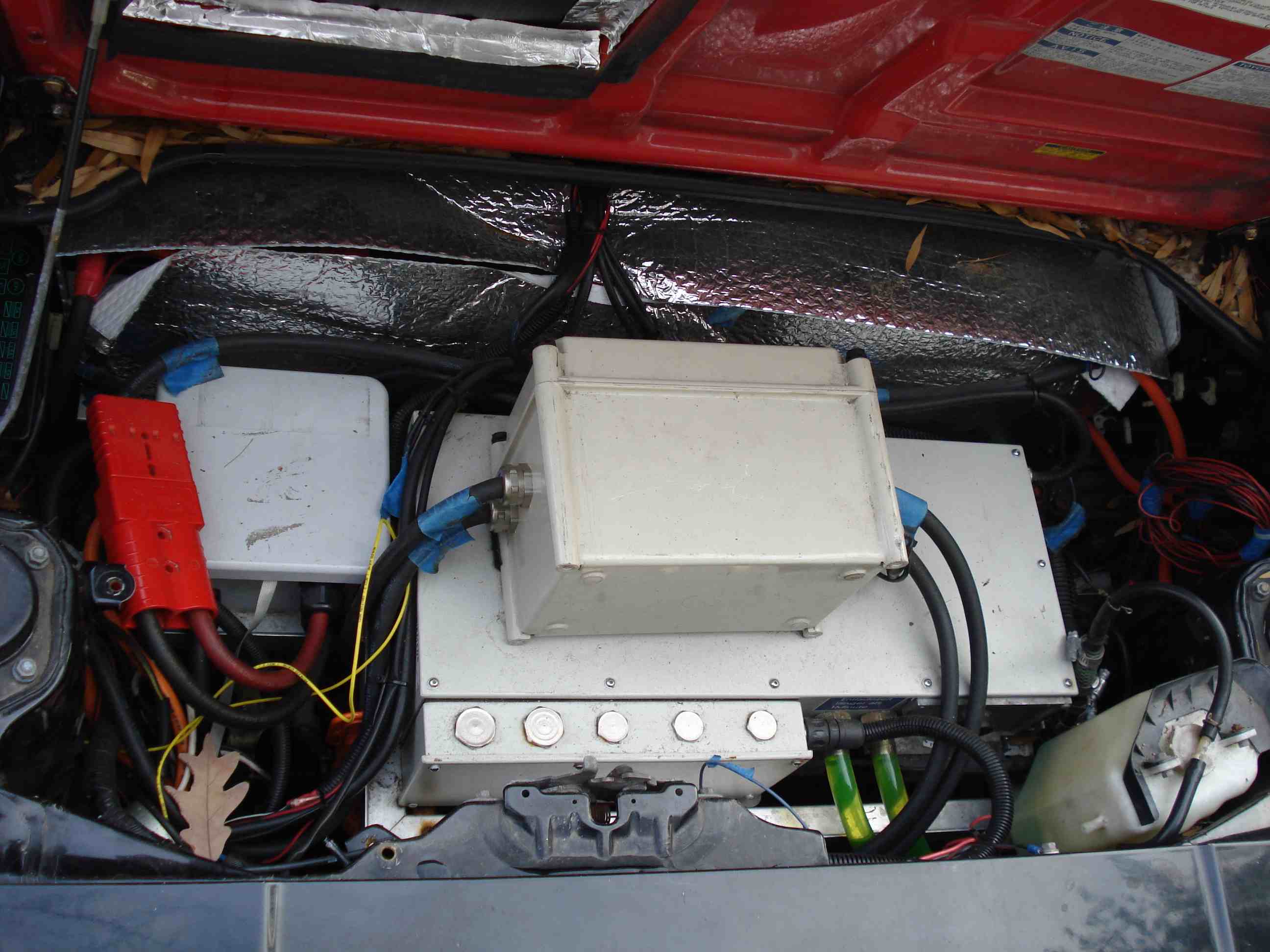

I had left the eMR2 in the garage last year after pushing the throttle produced clicking noises from the motor bay rather than any forward motion. I figured the noisy transmission had finally given out and embarked on the rebuild of the spare unit, something I had wanted to do in any case. I had entertained the possibility that the coupler may have been damaged but considering how sturdy it was it didn’t seem like a likely possibility.

Only last week did I finally drop the drivetrain out of the car to separate the motor from the transmission to take a closer look and it was a surprise. The transmission still rotated freely so the theory that a bearing had seized or other catastrophic internal damage occurred didn’t appear to be the problem. The pile of black powder settled at the bottom of the bellhousing did look out of the ordinary, though. The coupler had also shifted towards the transmission and I could see the mangled remains of the self-locking retaining ring pitifully dangling from the input shaft. The coupler had been laterally constrained by the end of the splines on the motor shaft and the apparently completely inadequate washer at the other. Figuring there not being much possibility of the coupler wandering, I didn’t use something more substantial like a clamp collar but more secure positioning will be incorporated inyo the new design. Examining the coupler produced the first clue; both splines had stripped completely and one of the pins had a chunk torn away. Tearing material away from a hardened pin isn’t the easiest task.

The electric motor puts out more torque than the four cylinder but considering I wasn’t hard on the car and it had only travelled about 100 miles it didn’t make sense that the splines would be completely destroyed in so short a time.

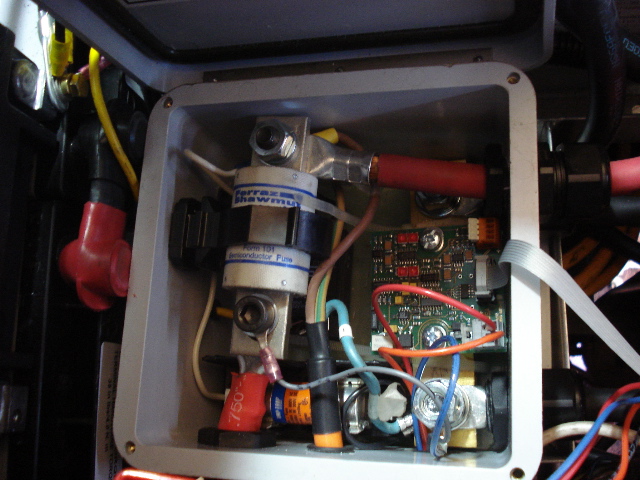

It was then that I noticed that the collar around the transmission input shaft revealed a lot more of the shaft than I remembered. Compared to the rebuilt unit there was at least half an inch missing. That’s when a closer look at the pins on the coupler revealed discoloration from high temperatures and wear on one of the pins that had slightly backed out.

Apparently the motor was working double duty as a metal lathe, grinding the coupler against the transmission collar and absorbing enough power to flatten the coupler splines. So that’s where all the power and range went.

The ground-down input shaft collar...

On the bright side, at least the destroyed splines were on the coupler rather than the motor, which would have been a far worse situation. I thought about getting the coupler hardened but this situation is a good reason not to do that. It’s much more preferable for the more easily replaceable (though still expensive) coupler to absorb the damage rather than the motor or transmission.

...and what it should look like

During the design stage a couple years ago I had also developed another coupler that incorporated the shock absorbing hub from the original clutch but went with this design based on its simplicity. Back then it didn’t seem like the spring hub was necessary as there would be no transmission shifting and the electric motor wouldn’t produce the internal combustion vibrations that the sprung hub is designed to moderate. Now it appears that retaining the sprung hub is a good idea to relieve the unhardened splines of shock loads so they can live a less stressful life. There’s additional insurance in the fact that the spring hub can absorb a little angular misalignment just in case there’s some relative motion between the motor and transmission.

I brushed off the old design and incorporating a way to constrain the coupler on the shaft so it doesn’t slide around again. The spring hub will be harvested from a sacrificial clutch disc that’s arriving within a week.